News & Reviews

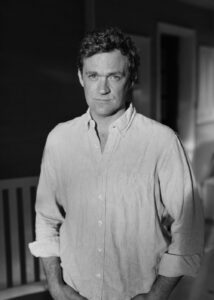

Patrick Radden Keefe

Patrick Radden Keefe is one of the most acclaimed masters of literary journalism. His books range from The Troubles in Ireland (The Prize-winning Say Nothing) to an expose of the family that gave us opioids (Empire of Pain: The Secret History of Sackler Dynasty). His New Yorker profiles of “Grifters, Killers, Rebels and Crooks” are collected in his new book Rogues, one of our top picks for 2022. Co-owner of Bookoccino caught up with the globe-trotting Patrick Radden Keefe for a chat about journalism, investigative reporting and how to craft a page turner.

You have a masters in international relations from Cambridge, a masters in science from the London School of Economics, and a law degree from Yale. What made you decide to become a journalist?

You have a masters in international relations from Cambridge, a masters in science from the London School of Economics, and a law degree from Yale. What made you decide to become a journalist?

I always wanted to be a journalist, and more specifically a New Yorker journalist, going right back to when I first discovered the magazine as a teenager. But, as I soon learned, it was one thing to have the aspiration and quite another to make it a reality. It took me years and years of pitching and rejection before they finally gave me an assignment, and because I enjoyed being in school and felt that I should probably have some sort of backup plan in the event that the New Yorker did not come to its senses and finally hire me, I ended up accumulating graduate degrees until they finally accepted a pitch.

Is there a difference between a journalist and a writer?

I don’t get too hung up on the semantics. I know that what I do has a certain literary ambition, a desire not just to relate information but to capture character and scene and drama in an artful way. But at the same time, there is an empirical rigor that comes with journalism (good journalism, anyway) which I hope means that the reader can trust what I am relating. My books have extensive endnotes, though I’m no academic; the notes are there so that the skeptical reader can check my work. Ideally, one sort of reader can just inhale the book as if it were a novel — a frictionless reading experience — and another sort of reader can be checking endnotes and auditing my sources and engaging with the text in a very different way.

Mark Twain said that ‘truth is stranger than fiction,’ adding, with his dry humour, because truth doesn’t have to stick to the facts. You do stick to the facts, but your writing is more suspenseful, more compelling, than fiction. What’s your secret? How do you turn your prodigious research, and into a compelling narrative?

You are very kind. Story always comes first for me. I think we are hardwired, from the cradle, to absorb information best when it is related as a narrative. So I’m always on the lookout for interesting characters, and narrative twists and turns. I grew up reading detective fiction — Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers — and I freely borrow from the toolkit of the spy novelist or the mystery writer. I get frustrated, as a reader, by books that feature copious research but little regard for storytelling. As a writer, I don’t take the reader’s attention for granted for a paragraph, much less a page. The challenge becomes, how do you distill years of complex research into a really seductive yarn? One of my little secrets, which I discovered rather late in the game, is that if there is some section that I have been putting off writing because it feels like obligatory exposition, and I’m bored just thinking about it, then I should probably just cut it. If it bores the writer a little, it will bore the reader a lot.

Which is harder – reporting a story, or writing it?

Reporting. By far!

What writers or books, fiction or non-fiction, do you read for guidance, or inspiration, in your own writing?

I read a bunch of my New Yorker colleagues, past and present: Calvin Trillin, David Grann, Larissa MacFarquhar, Rachel Aviv. I study the work of Robert Caro. I look to novelists, from Virginia Woolf and  Vladimir Nabokov to contemporaries like Colson Whitehead and (a recent discovery for me) Claire Keegan.

Vladimir Nabokov to contemporaries like Colson Whitehead and (a recent discovery for me) Claire Keegan.

Your Rogues gallery ranges from the Mexican drug king El Chapo and a neurobiologist who killed three colleagues with a 9 mm Ruger in Alabama, to a Wall Street financier who made millions from insider trading and Anthony Bourdain. How do you choose which Rogues to write about? And who’s your favourite Rogue?

Bourdain is the one odd fit in this menagerie, but he had, as I say in that piece, “a talent for badassery,” and I suspect he would have been delighted to be included in such a gallery of reprobates. I’m drawn to people with forceful personalities who create lives that are at the edge of what we would think of as conventional morality, and sometimes well outside of it. I don’t glorify these people, but I do want to understand them, and particularly, to understand how they regard the often horrible moral choices that they make. What is the story that they are telling themselves? One of the big themes I keep coming back to is the human capacity for self-delusion.

You explore all of the gray areas of a life in crime, considering the provenance of crime and affording your rogues a humanity they deny their victims. Do you struggle to balance the scales when you put together a piece?

You’ve put your finger on one of the big challenges of this sort of writing. I don’t think there is much value in me delivering a sermon in which I simply condemn these people without seeking to understand them. I also think that there is a certain comforting moral vanity in assuming that such people are just born evil and therefore different, in some fundamental way, from you and me. The truth is that most of us stray in small ways from the righteous path, and some of stray in large ways. It’s all about the angle of deviation. When I wrote a book about the Troubles in Northern Ireland, it was important for me to capture the romance of joining the IRA as a teenager in the 1970s, because if you don’t fully reckon with that, you won’t understand why people did. There was a glamor in it for the young recruits. So as a writer, the challenge becomes, how do you capture that glamor without glamorizing paramilitary violence yourself? It is a fine line, but one I think about more than any other when I’m writing these sorts of stories.

You have a remarkable ability to get people to talk to you — perhaps most strikingly the parents of Amy Bishop, the professor who murdered her colleagues in Alabama. Many years earlier Amy had shot her 18-year old brother, which had basically been covered up. You got her parents to talk about the shooting, which they claimed had been an accident. Reading this brought back Janet Malcolm’s famous, and contentious, observation that journalists are essentially con artists who seduce people into telling them what is not in their best interest. Do you sometimes feel uncomfortable when interviewing people? Do you ever wonder what makes people talk to journalists?

I think most people want to tell their stories. They want to be understood. This is, in some ways, a great advantage for journalists. One of the challenges we face is that people sometimes lie to reporters, or they lie to themselves. In the case of Amy Bishop’s parents, that was a story about denial, and it is absolutely uncomfortable to have deeply intimate and painful conversations with people who are very deep in denial. Because when you write the story, your allegiance is not to them, but to the truth. They may perceive the story as a betrayal, insofar as they have told one sort of story and you have told another. But I don’t see that as a betrayal, and much as I revere Malcolm, I don’t buy her characteristically provocative suggestion that it is a con. You approach people with an open mind and talk to as many people as you can, then you assimilate these different viewpoints, cross-check everything, and come to your own conclusion. That’s not some trick or double cross. It’s the job.

In Empire of Pain, you expose the Sackler family, which made billions from the promotion and sale of opioids, creating an epidemic of death and destruction. While the name has been removed from a few museums and universities around the world, no member of the Saone has been criminally prosecuted. Does this illustrate the limits of even the best journalism?

I’d say so, yes! Empire of Pain is a book not just about this one family behaving badly but also about a system in which there is often near absolute impunity for the billionaire class. So I knew from the outset that this would be a story in which the bad guys get away with it in the end. I take some satisfaction in having contributed to the public conversation about the Sacklers, and their reputation is certainly not what it was back in 2016 when I started my research. But as we’ve seen in so many different contexts lately, it is one thing to document wrongdoing and quite another to achieve any real measure of accountability.

Your mother is from Melbourne. When are you going to write a book set in Australia?

I would love nothing more! I’ve been on the lookout for the right story. You know the ingredients: big personalities, crime and corruption, secrets and lies. If anyone has a good lead, get in touch!

Say Nothing, Empire of Pain and Rogues are available in-store now.